As AI Enters the Creative Arena, Co-Creation Must Lead the Way

From Prototype to Assistant: How AI Became a Creative Agent

Guest post by Severin Zugmayer, New Renaissance Ventures

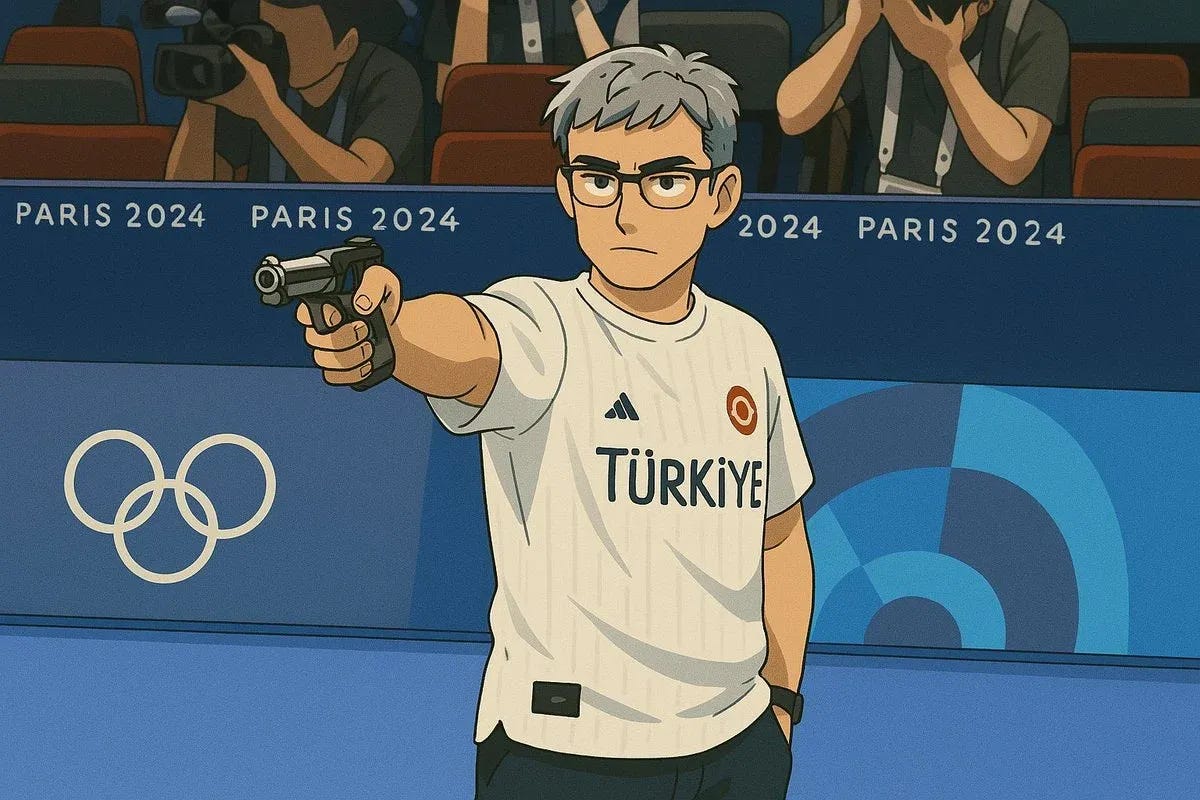

In March 2025, the internet overflowed with AI-generated images echoing the charming style of Studio Ghibli.

The trend went viral after OpenAI introduced GPT-4o, the first image generator built into ChatGPT. Only a few years earlier, in 2021, DALL·E had difficulty generating a basic image of a “man riding a bicycle’’. What has changed between AI’s early limitations and today’s world, where anyone can generate one-prompt, stylised visuals, is not a minor technical leap but the emergence of a new creative interface.

With models like Midjourney, Flux AI, and Stability’s custom-trained tools, we are seeing near-cinematic precision and stylistic imitation so compelling it blurs the line between homage and invention. This is happening because diffusion models are becoming faster and more coherent. Datasets have expanded while training has grown more refined.

But there is something else that technical advancement allows. With the democratisation of AI tools, AI began to participate not just in content creation, but in cultural expression. This isn’t a niche phenomenon. According to a report by UBS analysts, ChatGPT reached 100 million monthly active users within two months of launch, surpassing Instagram's thirty-month growth and TikTok's nine-month growth to become the fastest-growing consumer app in history. As the UBS analysts noted, “In 20 years following the internet space, we cannot recall a faster ramp in a consumer internet app’’. This explosive adoption reflects both generative AI product-market fit and an unprecedented cultural receptivity to the new technology.

And that receptivity shows up in the cultural expressions we now take for granted. The Studio Ghibli trend wasn’t only a fast image generation skit. You can look at it as a symbol of a new global creative canvas, made possible because millions of people had easy access to AI tools and knew how to use them.

However, beneath the playfulness lies a deeper tension, a fight between authorship and user-generated content. The Ghibli visual language was chosen by millions of people, who then added their own spin to a copyrighted style and fed the content back into the algorithm. Many creators and right holders, like Ghibli’s father Hayao Miyazaki, have raised concerns about AI-generated media mimicking original material’s distinctive style. They view generative AI as a threat to artistic integrity and a potential infringement on copyright.

At this point, we are no longer looking at AI tools in the creative domain as products that simply help you create content faster. For all intents and purposes, we live in a new world inhabited by silicon cultural actors that are semi-autonomous and have the ability to re-work, stylise, curate, and even generate art that moves people. The question is no longer whether AI can make something beautiful, but what happens when AI has the potential to become a creator?

That same tension between authorship and originality is not confined to social media trends but it’s now moving into the heart of the art world itself.

In 2022, artist Jason M. Allen won the Colorado State Fair fine arts competition with Théâtre D’Opéra Spatial. Nothing strange with this, until you learn Allen made the artwork using more than 600 prompts in Midjourney, and adding a few final edits in Photoshop.

AI creativity is not limited to what we see on a screen or in a gallery. Every media,

including music, audio, films and even storytelling are being affected by the same forces that are challenging traditional human creativity in the visual arts. AI is becoming increasingly essential to our tools and workflows to inspire, interpret and co-create, not just to automate.

At the current stage, AI is more than a clumsy assistant. Generative AI tools can serve as a mirror of our minds. Whether that mirror truly reflects culture or merely mimics it depends on how we design, direct, and collaborate with these systems.

When AI Hits Its Creative Limits

Generative AI feels like magic until you ask models to be truly original. AI can produce poems in the surreal style of Queneau, render a painting à la Kandinsky or generate romantic melodies like Beethoven. It can blend, imitate and extend, but when it comes to creating new genres, a new style or a new conceptual grammar, it stalls.

More than a technical limitation, it’s a creative bottleneck. That matters, if we expect AI to be more than a stylistic copy-paste machine. British philosopher Margaret Boden offers a way to see why this happens. She distinguishes between two modes of creativity:

Exploratory creativity: working within an existing creative framework.

Transformational creativity: changing the rules of the creative game itself.

Exploratory creativity is where today’s AI shines. It can produce endless variations, remix styles and iterate faster than any human, even on high dosage of MDMA. But it can’t yet break the frame the way Picasso’s cubism did to realism, or jazz to classical music. Looking outside traditional arts, Minecraft created a whole new genre of open-world sandbox play. Those leaps into the unknown, what Boden calls transformational creativity, still belong entirely to the descendants of the apes. That's the paradox at the heart of AI-generated culture: speed without ultimate originality.

As one of the founders of OpenAI Andrej Karpathy puts it, “Hallucination is all LLMs do. They are dream machines”. You give them a prompt, and they return a surreal riff, sometimes nonsensical. Sometimes brilliant. Even if the output, at times, lacks visual coherence. In that sense, hallucination may be the closest AI comes to novelty, creativity born of chance, without authorship.

The viral Wes Anderson-style movie trailer generated by Youtuber Curious Refuge is an example of a hallucination that caught creative fire. Its charm lies in the unexpected references the model wove together under human guidance. The trailer is a quirky mash-up of Star Wars characters, shown in quick succession in Wes Anderson’s signature pastel palette and symmetrical compositions.

AI’s knack for borrowing aesthetic patterns from different sources and extrapolating fragments of innovation can be mistaken for originality. Generative speed can also trick us into thinking we are seeing something new. But a million sketches in an already existing style are hardly the start of a new artistic movement, as the Ghibli trend showed us.

A generated output with hallucinations without intent is often just noise. Yet in human circles, isn’t it often the case that what we initially see as noise, through exposure, becomes a pattern, and that such novel patterns account for transformational ideas? The first people who saw Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon likely perceived uncanny noise in the deformed nudes. Could those machine hallucinations be the spark of unintentional, transformational creativity?

Let’s be honest… this is a charitable interpretation of what is going on with these machines. The lack of intention in generative AI is a barrier to creativity. Intention is a key ingredient for being creative. The least deliberate an AI is, the more random noise it generates. This limitation shows up most clearly in media that heavily rely on aesthetic judgement and cultural intuition. Even the most advanced text-to-image models, such as DALL·E 3, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion, are still pattern engines. They can capture a fragment of reality, but don’t grasp the emotional logic that makes it matter. They don’t know why Grave of the Fireflies leaves us wrecked, curled on the sofa, eating chocolate ice-cream to cope. Or why The Last of Us keeps us into the game, pulled in by fragile human bonds set against the fight to survive.

The difference between surface imitation and real emotional understanding matters. The imagery of the Grave of the Fireflies and the emotional arcs of The Last of Us likely came from the experience and contradictions of the people who made them. Style alone can’t get you there. Without that depth, the result might still be compelling but far from being transformative.

Exploratory creativity has value, because it can spark ideas, refine aesthetic and speed up iteration. But let’s not confuse it with breakthrough innovation. Transformational creativity needs a rule change, a rupture, not just a polished rework of what’s already there. Ruptures grow out from frictions, contradictions, disobedience. For now, they don’t come from a clever prompt but from human acts of conceptual revolt.

Until AI can break its own rules, or we teach it how, humans have to stay in the loop. To steer and to supervise. To insist on originality when convenience would be easier. If we let AI set the tempo of culture, we may find ourselves accelerating towards sameness, just faster than ever before.

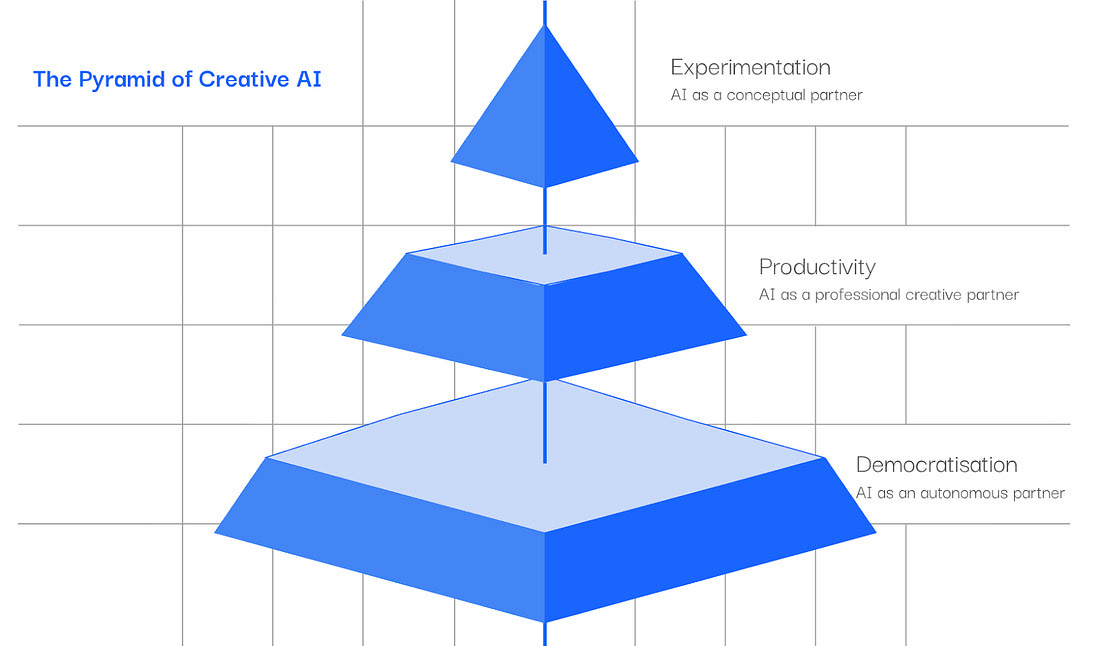

The Three-Layer Market of Creative AI

Creative AI doesn’t work the same way for everyone. A TikTok creator chasing clicks wants something very different from a filmmaker exploring a new visual language. Or a brand designer building emotional nuance into a logo. These people belong to different markets and have divergent ideas of what creativity means. So, if we want to understand AI’s role in culture, we can’t just look at what it’s capable of. We have to ask who is holding the brush, and what they are trying to paint.

We can map the creative ecosystem by breaking it into a pyramid cut into three layers. Each area features a distinct balance between AI autonomy, human intent, and the kind of creativity that matters most.

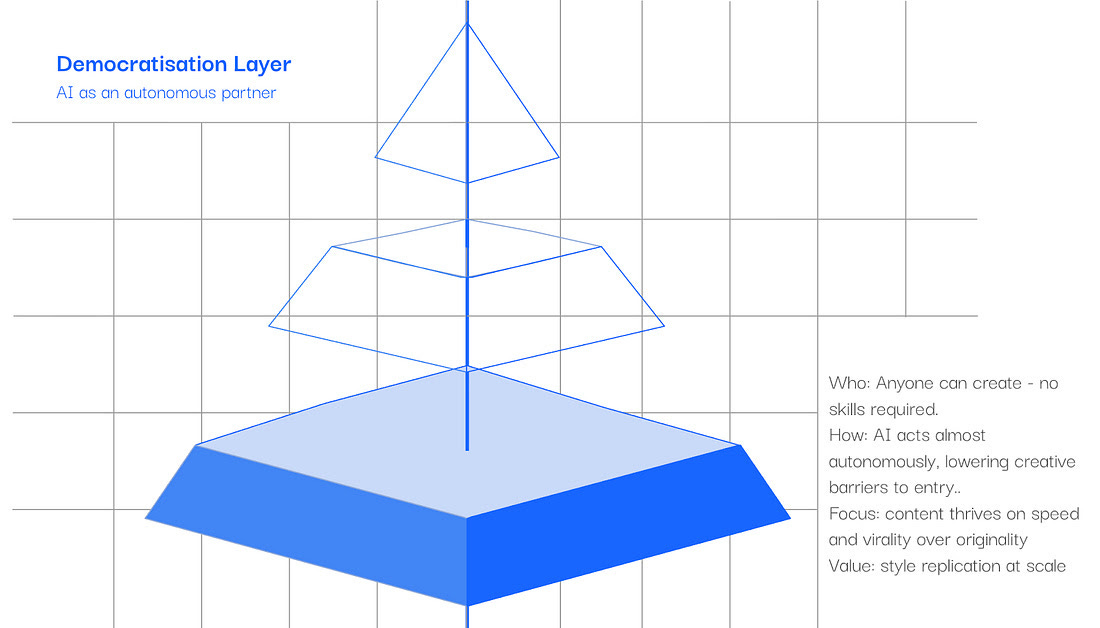

Level One: The Democratisation Layer

This is the base of the pyramid. It is a chaotic space filled with TikTok edits, AI-mashups, and memes. Have you heard of Tung Tung Tung Tung Tung Tung Sahur? Culture mutates in real time and attention, which is the ultimate currency, outruns deliberate artistic intention.

AI thrives here as an almost autonomous tool, not a partner. Creativity is fast, messy, and remixable. A content creator can generate a nonsensical video, drop in an AI voiceover, and hit a million views before dinner.

The generative AI tools in this layer lower the barrier to entry for creative media production. It started with text (ChatGPT) and images (Ideogram, DALL·E), then moved to automatic music generation (Suno, Udio) and video (VEO, Runway).

This is a juicy market predicted to expand at lightning speed, from $10.6 billion in 2023 to $109.4 billion by 2030. Run the math and you get a 38% year-over-year growth rate. This is the sort of growth VC investors are looking for.

Low friction fuels this layer. It also makes it risky. The Studio Ghibli trend showed how quickly a style can be copied at scale. Millions of users generated Ghibli-inspired scenes without pausing over copyright or artistic intent. To some, the skit was playful and harmless. To others, it was mass replication without respect for the artist. For OpenAI, it was a great marketing stunt.

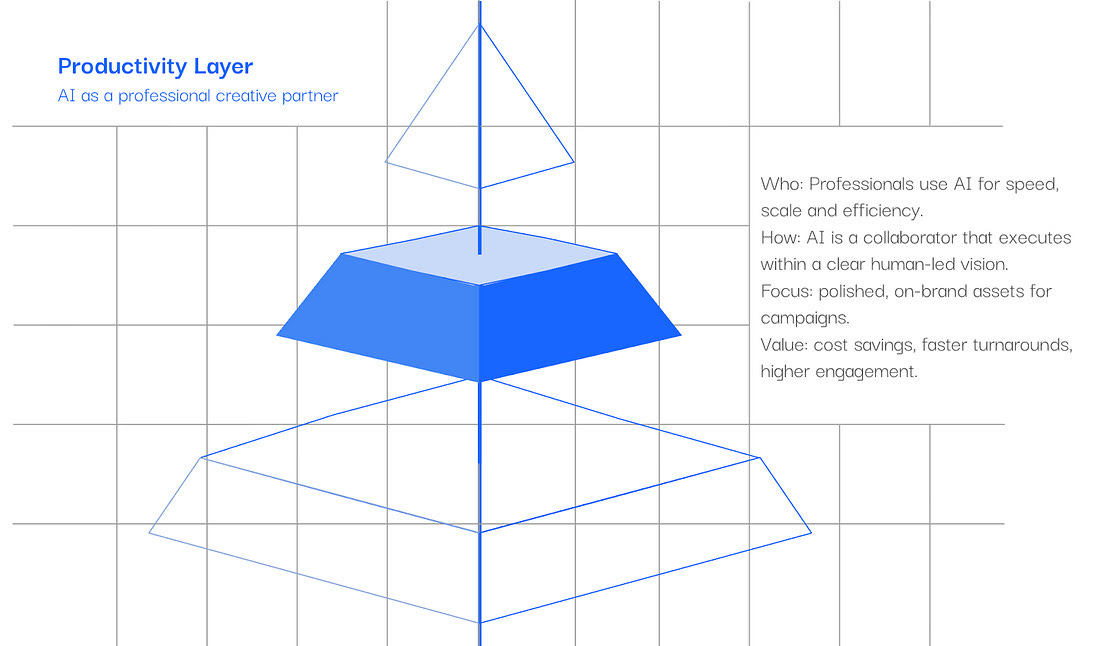

Level Two: The Productivity Layer

In the middle of the pyramid sit brands, creative agencies, and professional content teams. They are not looking to be the new Picassos. They need assets aligned with brand guidelines and optimized for social engagement. Fast turnaround is the ultimate value.

Here AI works like a production engine, scaling campaigns, cutting timelines and trimming costs without sacrificing polish.

Consider Kraft Heinz’s “AI Ketchup” campaign. The team fed DALL-E 2 with funny prompts like “ketchup in space”, “ketchup as a superhero”. The AI generated playful visuals that consistently echoed Heinz’s packaging, even though the creatives didn’t input the company logo, or references to its brand. Evidently, DALL-E 2 never fails to put Kraft Heinz’s ketchup when it eats french fries. The campaign turned AI into a brand ambassador. 1.15B people viewed the campaign, with 38% more interaction than usual. A viral trend started, with a 25x return on investment.

In this layer, AI handles the heavy lifting. Unlike in the base layer, AI is a collaborator, not an almost autonomous entity. Human teams keep the creative direction on course, serving a clear, often business-oriented vision. That human intention can then be implemented with a degree of autonomy by a generative tool. Still, humans have the final say in filtering the results.

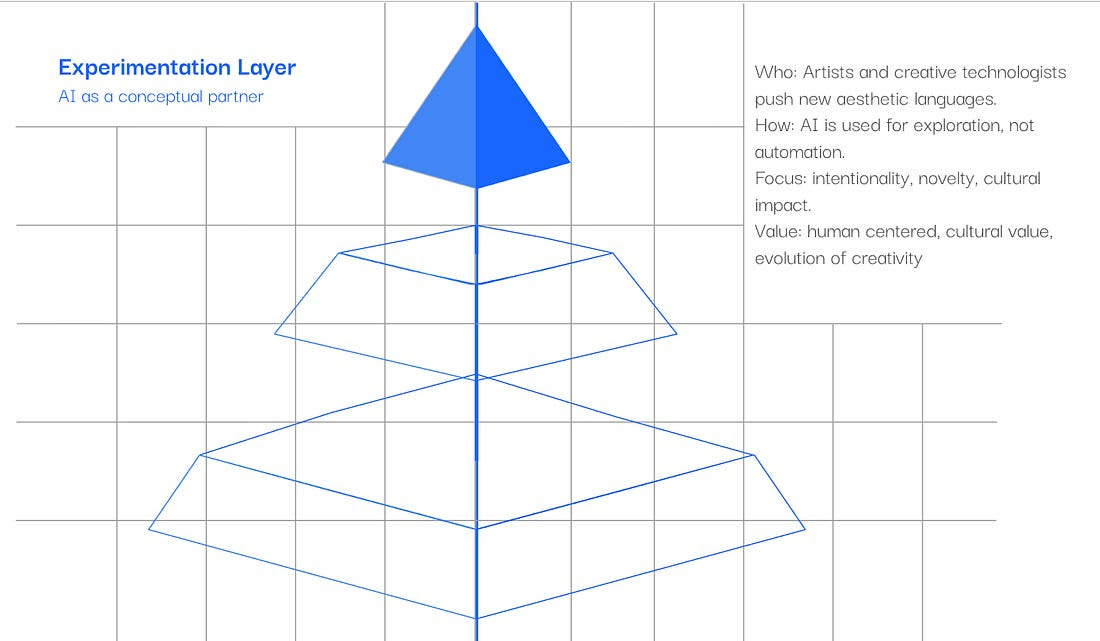

Level Three: The Experimentation Layer

At the top of the pyramid are the outliers, the artists, and creative technologists who treat AI as a medium for experimentation. They aren’t chasing brand consistency or viral reach. They are probing for new aesthetic languages, questioning assumptions and testing what media can be.

AI is a creative companion. Artists in this layer don’t want the machine to replace them. They want generative tools to be a collaborator in a conceptual duel, something to challenge or be surprised by. The product of this layer can be transformational. Artists here don’t care about scale, or efficiency. They go on a journey of research and experimentation that sometimes may lead to creative novelties that shift the ground.

Refik Anadol’s installations, Unsupervised at MoMA and Large Nature Model, are prime examples. Built from datasets ranging from weather systems to satellite maps to biometric signals, his works translate information into immersive digital abstractions. The results are hypnotic, strange, often sublime. But Anadol never hands over control to the machine. He curates the datasets, guides the model, and shapes the narrative arc, directing the AI’s dreams, rather than being led by them.

At the tip of the pyramid, the collaboration between humans and AI is fragile. And not everyone trusts it. As Arthur Jafa has warned, “AI can do everything, but it doesn’t know why to do anything.” For creators at this level, intention isn’t negotiable. Without it, AI risks becoming a feedback loop of past styles, technically brilliant, but conceptually flat.

Uniqueness and a personal point of view isn’t a bonus. The only way AI gets close is with a human provocateur in the loop, someone willing to take the risk, frame the question, or walk away from the algorithm entirely.

What does the three-layer pyramid introduced by generative AI mean for the creative industry, and for those funding it? Each layer plays a distinct role:

Creators in the Democratisation layer drive cultural volume and everyday aesthetics.

Practitioners use generative AI to meet the pace of digital attention.

Experimental artists push the boundaries of art and, by extension, culture itself.

No layer is more important than the others. Treating them as interchangeable flattens the creative AI ecosystem we are trying to grow. Acknowledging their differences is where the real business opportunities lie. We don’t need a single creative AI for culture, a system that rules them all, spanning every layer. The market needs a stack of AIs tailored to each level and medium: tools that support co-creation at the top, autonomous generation at the base, and smart augmentation in between. Respect those differences, and the ecosystem will thrive not only on what AI can do, but on what people need it to do.

Why Human-AI Co-Creation Matters

We now have all the ingredients to explain why human, AI interaction is key for new forms of creative work, and for the creative industry at large. Strangely enough, we can make this point by revisiting the most viral trend of early 2025.

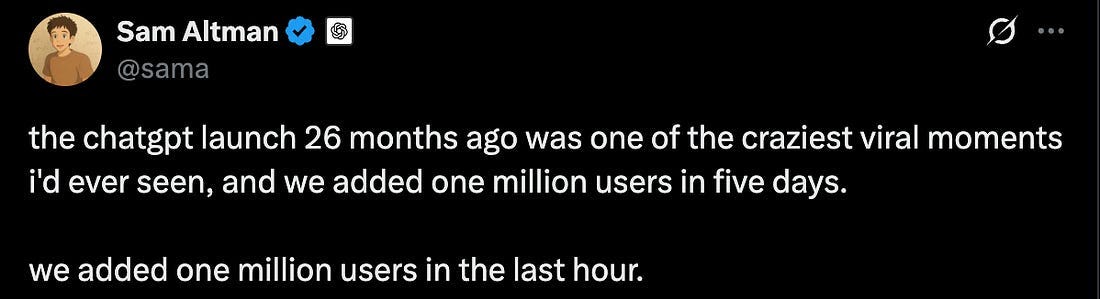

The Ghibli trend was built on the legacy of the beloved Hayao Miyazaki. That success which, as Sam Altman said on X, brought over a million users to OpenAI in a single hour, reveals something interesting.

The reason people embraced the Ghibli style and applied it to their personal pictures and favourite images is because that aesthetic was created by someone who had something to say. Hayao Miyazaki invented a style that didn’t exist before. It took decades of obsessive worldbuilding, iterative visual design, and philosophical depth to develop a visual language capable of expressing wonder, grief, and spiritual ecology, layered with Japanese folklore and post-industrial melancholy.

The Ghibli look is memorable because it’s personal. The aesthetic is so full of meaning that it has endured and had time to settle into people’s imaginations.

Without a creator’s assistance, generative AI offers only surface without substance, fast replication that can entertain for a time but, without authorship, will not endure. That’s why the viral trend will fade in a few days, while Howl’s Moving Castle will last for decades, perhaps centuries.

So yes, AI can create. But without guidance, it produces the average.

An experiment by MIT’s Media Lab asked 50 university students in Boston to complete writing tasks. Some worked on their own, while others used ChatGPT. The AI-assisted students produced writing that was coherent and polished but also more uniform and less distinctive. Brain scans of this group also showed lower cognitive activity. The tool shaped their thinking, not only what they wrote.

AI lowers the mental effort needed to express ideas, rewarding quick completion over deeper exploration. That’s the trade-off when we mindlessly default to AI: speed comes at the cost of perspective. Coherence replaces contradiction. The results satisfy but rarely surprise.

Boden’s framework helps us see why Refik Anadol’s AI installations do more than remix data. They guide audiences to experience environments in new ways. That’s the leap from exploration to transformation. The most innovative artists working with AI are designing systems, shaping behaviour, and embedding their voice in the model.

In the hands of intentional creators, AI becomes a medium. For artists, and, to varying degrees, for practitioners and content creators, active control of the machine should be a feature, not a fallback. That’s how culture moves forward instead of getting stuck in an average soup.

Affording generative AI tools with creative control is where the most interesting opportunities for startup founders lie. Let’s take a look at some of these products already on the market.

Designing the New Creative Stack

Companies developed most of today’s generative tools for instant results, not sustained creative exchange. They are optimised for hitting “generate” once, not for the back-and-forth that makes ideas deepen.

Generative AI products still treat creativity as a transaction where you type in a request and hope for the best. They autocomplete their way through culture, recombining what already exists without any sense of why it matters.

The result is often a hollow remix of yesterday’s ideas. If we care about augmenting human creativity with AI, rather than compressing it into sameness, we need a different foundation. The two pillars are: more controllable interfaces and models, and a new system of incentives that promotes human-AI interaction. Startups should develop controllable generative products that make co-creation become more than a buzzword to pique the investors’ interest.

At the heart of the problem is a mismatch between how creatives work and the way AI developers build their products. Developers don’t understand creatives. Or, at best, they have a simplified understanding of their processes.

Creative thinking is iterative, non-linear, and blurry. It involves friction, exploration, and aesthetic judgment. Yet most current generative tools flatten that process into a single step, as if a handful of words could capture an entire visual language or narrative arc. There is no way inputting “melancholic city at dusk” into Midjourney will ever stand in for the months it takes a filmmaker to find the right light, the right angles, and the right silences.

The biggest flaw in today’s creative AI tooling is a user experience that strips away the messiness of real creative work. Feedback loops, visual thinking, instinct, taste, and tension get replaced by the “prompt-in, image-out” shortcut.

If we keep building systems that prize consistency and speed over control and subtlety, we edge toward cultural uniformity. The base of the pyramid may be OK. But, for sure, the mid and the tip will never fall in love with these tools. Raising the bar for creative work means redesigning the stack from its principles, building tools that shift from task executors to thought partners, but only when creators take the lead.

Designing systems that reflect how creative thinking actually happens would benefit from considering:

Multi-modal input: where sketches, voice notes, gestures, and reference material inform the model.

Real-time feedback loops: where creators can guide, refine, redirect, or resist outputs as they emerge.

Spatial computing environments: where creative interaction is embodied, not abstracted to a keyboard

Contextual memory: where models remember your evolving creative voice

Meaningful provenance and attribution: so authorship isn't lost in the shuffle of auto-generation.

Some early-stage startups and established companies are already moving in the direction of AI-creators collaboration, exploring this shift.

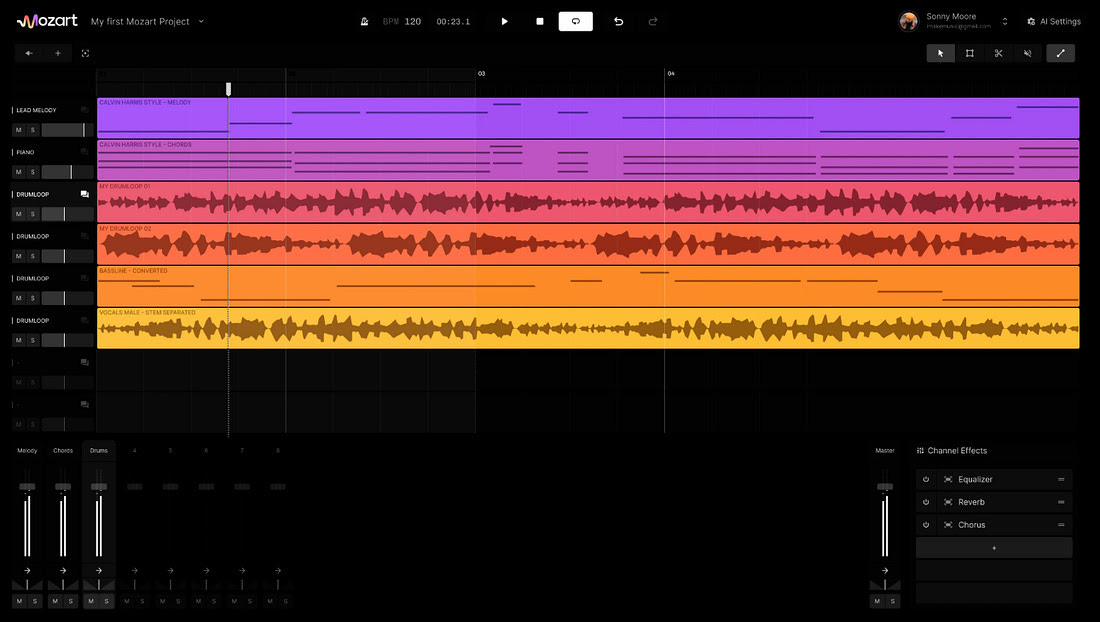

Take Arthos, for example, a startup backed by New Renaissance Ventures that is building Mozart AI. It’s a streamlined Digital Audio Workstation, like ProTools, designed for iterative musical composition. Musicians don’t input a command and wait for a track. Instead, they interact with AI-generated bits, create harmonies, push back against suggestions, and evolve their sound over time. It’s a real-time exploratory interaction.

Runway is building a creative operating system for the visual internet, combining timeline editing, real-time fine-tuning, and accessible professional tools.

Fable is turning generative AI into interactive storytelling infrastructure. Their work with AI characters is about persistent, intelligent agents that react, evolve, and retain information during a story. In doing so, the platform is exploring new possibilities for narrative systems outside of gaming and movies.

Toongether, in the New Renaissance Ventures portfolio, experiments with co-creation in short-form comics. It uses “reply-in-panels” threads and remixable panels to let multiple creators evolve a story together. This approach makes collaborative authorship part of the medium itself.

Toongether’s app lets users scroll through comics, play with drag-and-drop creation, and choose characters to build stories collaboratively. Image via apps.apple.com.

Despite this momentum, many essential points remain missing, like for example:

AI agents that adapt to a creator’s evolving process over time;

Interfaces that accept creative input in mood, movement, or metaphor, not just explicit commands;

Frameworks that secure attribution, rights, and value distribution for human-AI collaboration;

Product models that prioritise creative control over algorithmic optimisation.

This links back to the three-layer pyramid where AI-human creation is not one-size-fits-all. Trying to serve them all with the same product usually means serving none of them well. Instead, the creative stack should be layered:

Democratisation: high-volume generators for disposable, fast-moving culture;

Productivity: augmentation tools for predictable, brand-aligned output;

Experimentation: open-ended co-creation environments that evolve with the artist’s process.

Some companies already reflect this logic. Runway’s editing-first interface supports both content creators and agencies. Fable’s persistent AI characters hint at tools that can carry a story forward over weeks or months. On the democratisation layer, social co-creation platforms like Toongether illustrate how storytelling can emerge from collaborative, incremental contributions.

The strategic advantage lies in clarity of purpose. A tool built for the top layer shouldn’t compromise for the base. A base-layer generative engine shouldn’t pretend to be a medium for high-stakes art. Matching the product to the creative tier is what will let the whole ecosystem grow without flattening its differences, and allow startups to get to product-market fit faster.

The task ahead is to create tools that expand the scope of human creativity. Systems where authorship, whether human or augmented, remains central. That’s where durable companies will emerge. At the point where technology strengthens the human voice rather than replacing it.

Raising the Ceiling

We have explored what AI can generate and whether it can express, collaborate or remember. We have found that yes, generation is no longer the bottleneck. Models can already produce images, video, text, and sound but how AI is integrated into the systems that shape creativity itself is what matters now.

As AI moves from experiment to infrastructure we must ask; Who holds the controls? What kind of projects get funded? And how do we protect the integrity of the creative process through that transition?

If AI is going to play a primary role in creativity, the systems around it must do more than optimise output. They must create space for intent, interpretation, conflict, and emotion. Otherwise, we’ll have what we have now but faster, flatter, and more homogenous. This is a cultural architecture challenge that demands intentionality from every actor in the creative industry.

Infrastructure offers founders and investors the opportunity to use tools that support flexible, iterative workflows and which respect creative nuance. Depth and adaptability are the features that will be valued in the future more than speed alone.

As for platforms, they face a design challenge because the goal is creating spaces

that encourage authorship and experimentation. When systems invite contribution rather than passively delivering content, they become part of the creative process itself.

For creators, it’s a question of alignment. The best tools will deepen their work and support exploration. Friction, when intentional, can unlock refinement, originality and drive more meaningful outcomes.

And for all of us, it’s worth remembering that this creative stack is still early. The defaults we set today will shape what’s possible for the next generation.

We have a rare opportunity to resist flattening. To support divergence instead of standardisation. Especially across the layered creative market, where different creators, from short-form editors to experimental artists, need different kinds of engagement, not one-size-fits-all pipelines.

The real leverage isn’t in how much a model can do on its own. It’s in how well it responds to human intent, taste, and imagination. The work ahead is to build systems that make space for difference, and tools that help creators push beyond their obvious.

Most agree that generative AI lowers the floor for creative work. Now, we must raise the ceiling.

Thank you for sharing this guest post by Severin on EUVC! Great insights and glad to see VC funds holding onto the origins of venture capital that is to make asymmetrical bets on extraordinary people (even when low-key) ;)