Corporate venture capital isn’t just having “a bit of VC on the side.”

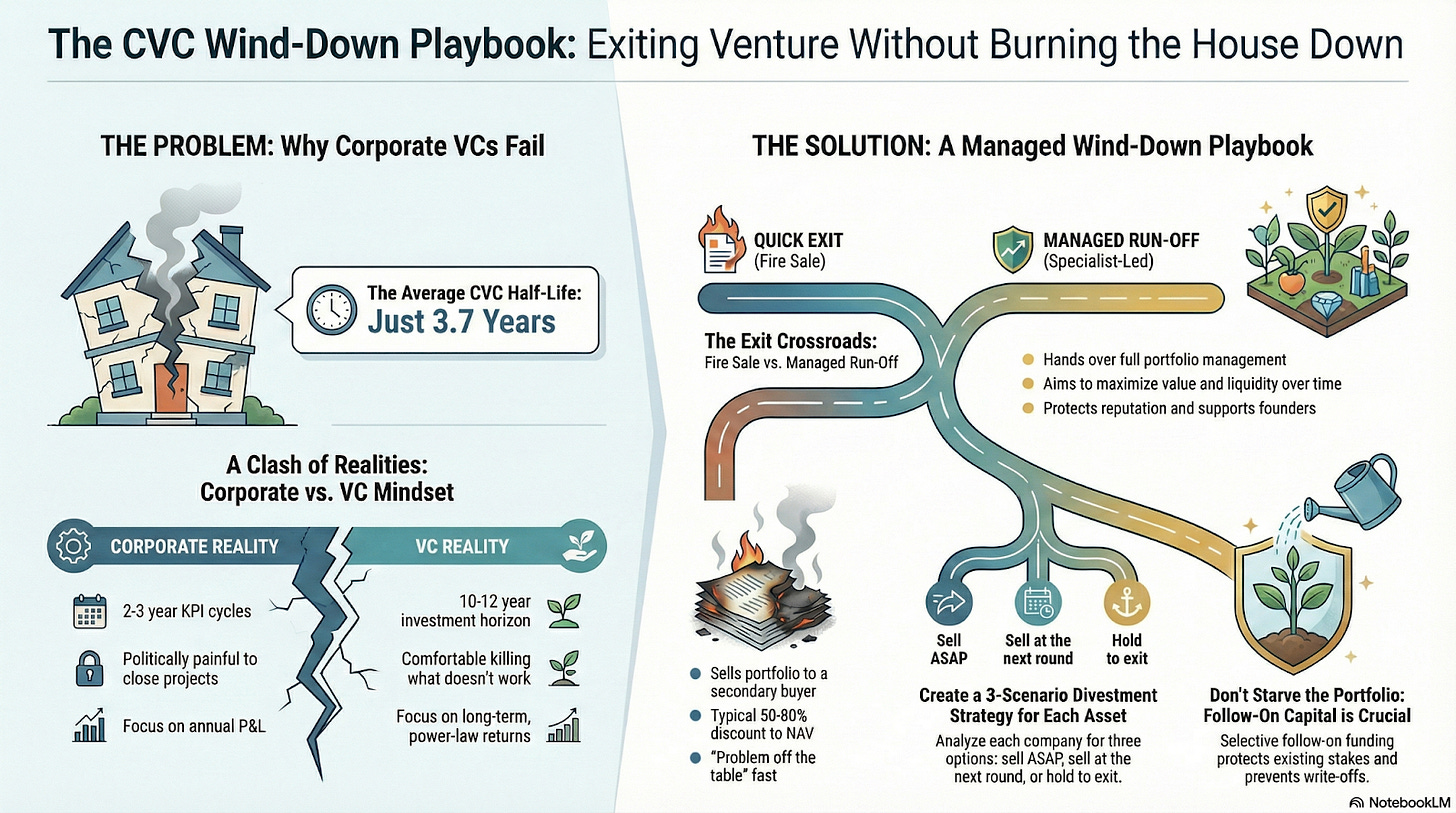

Done well, it’s a strategic lens on the future. Done badly, it’s a short-lived pet project with a half-life of 3.7 years and a trail of confused founders and annoyed co-investors.

In this episode, we sit down with Martin Scherrer, Partner & Head of Managed Funds at Redstone, alongside our own CVC lead Jeppe Høier, to unpack what really happens when corporates leave venture — and how to do it without destroying value or reputation.

Redstone runs a dual model: classic VC funds + “VC-as-a-Service” for corporates and family offices. Martin himself has lived three lives:

Inside Swiss Re’s CVC (later shut down)

As a founder of an insurtech in Switzerland

Now as VC & fund manager at Redstone across multiple corporate mandates.

This article distills the practical playbook and for the quick readers, here’s the TL;DR info graphic 👀

1. The Structural Problem: Why CVCs Keep Dying at 3.7 Years

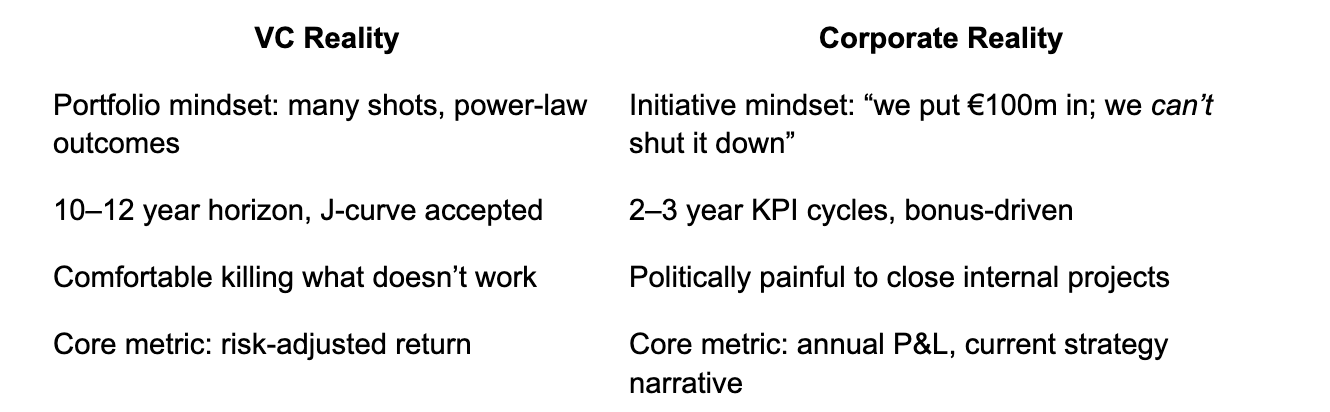

The starting point is brutal: most CVCs don’t die because venture doesn’t work — they die because corporates aren’t set up to think like VCs.

Martin’s own career started at Swiss Re’s CVC, a 60+ person team that was shut down two years after the dot-com bust and one year after 9/11. Strategy refocused on the core, performance looked bad on a short time frame, and venture was an easy victim.

Add today’s examples like Munich Re stepping away from CVC, and you see the same pattern:

short horizons + lack of VC mindset at board level = shutdown risk, regardless of actual portfolio quality.

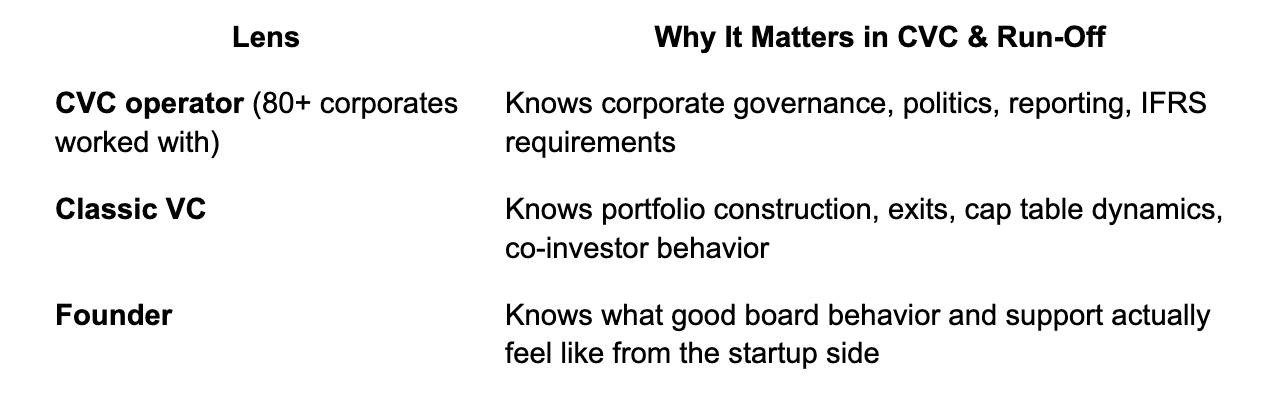

2. Redstone’s Positioning: Operator of Last Resort (and First Resort)

Redstone is not your typical venture firm, it can almost be understood as a VC asset management platform that:

Runs its own sector funds (fintech, deeptech, industry 4.0, etc.)

Manages corporate and family office funds (VCaaS)

Takes over CVC portfolios in run-off (SCOR, Helen, others)

The edge comes from three lenses combined:

This mix is what lets Redstone step in after a corporate decides: “We’re out of venture — now what?”

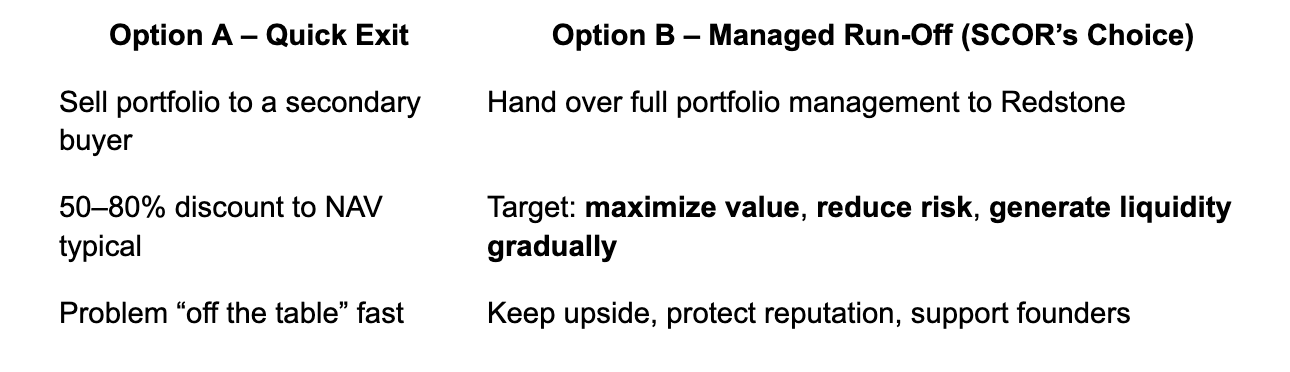

3. The SCOR Case: How to Exit Without a Fire Sale

In the episode, we dive deep on the SCOR portfolio as a central case study of how Redstone takes over corporate venture arms.

At the time, SCOR’s choice was not: “CVC or no CVC?” That decision had already been taken: stop new VC investments. Instead, the choice was:

SCOR engaged a Big Four advisor, ran a structured process, and chose Redstone to manage the full transition, including taking board seats and defining the divestment strategy.

4. How to Onboard a Run-Off Portfolio (in 3 Weeks)

Redstone’s work with SCOR shows how a run-off can be onboarded fast and properly.

Step 1: Intensive onboarding (≈ 3 weeks)

25 portfolio companies

No interaction with the old team

Deep dive into all docs, cap tables, board material and open issues

Step 2: Prioritisation & role mapping

Which companies are the biggest exposures?

Where are the urgent financing needs or crises?

Which Redstone partner is best suited for which board, by sector and stage?

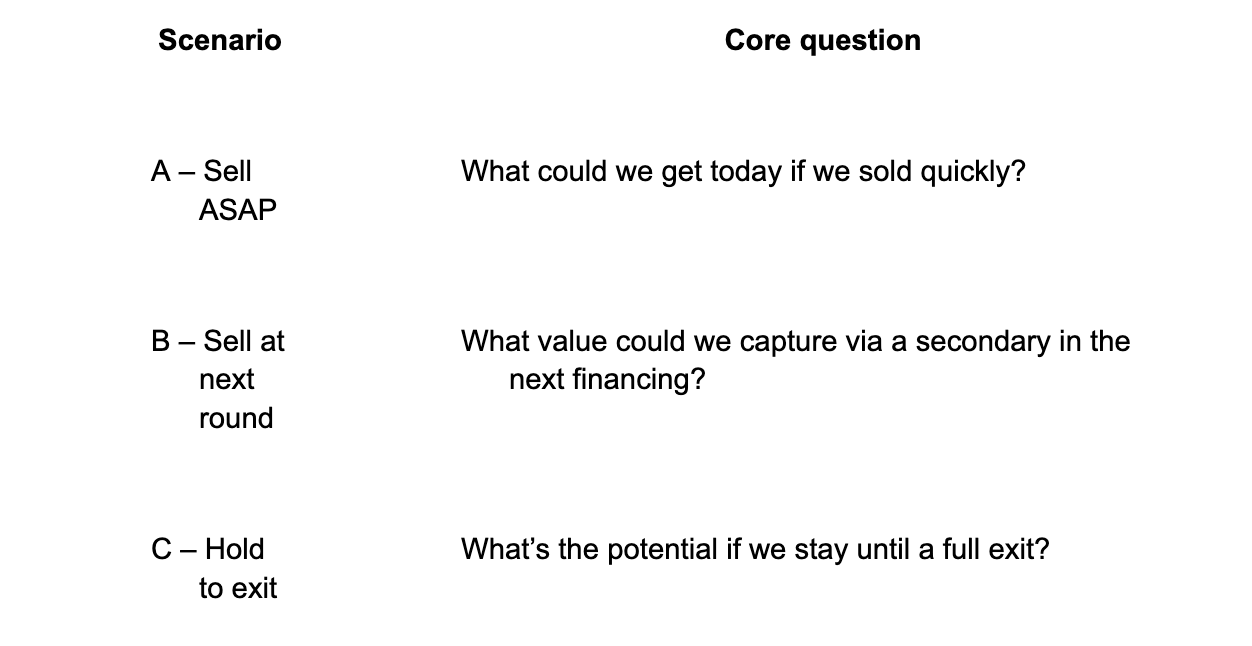

Step 3: Scenario framework for each company

For every asset, Martin’s team builds three clear scenarios:

This becomes the backbone of the divestment strategy: balancing risk, liquidity and upside over a 4–5 year horizon.

Step 4: Board & governance takeover

Redstone takes over the corporate’s board seats

Sets lean governance, decision-making rules and reporting (e.g. IFRS 9 for listed entities)

5. Why Follow-On Capital Still Matters in a Wind-Down

One of the most counterintuitive points in the conversation:

Even when a corporate is exiting VC, follow-ons still matter.

In all corporate run-off mandates Redstone manages, there is capital reserved for follow-ons.

Why?

Example: one company stuck between seed and Series A.

Only institutional investor = the corporate.

No new external VC interest.

Without some bridge money, it dies.

Redstone convinced the corporate to invest a few hundred thousand more. That:

Attracted additional angels to extend runway

Gave time for the company to hit milestones

Enabled two new, strong VCs to lead a proper round later

Result: corporate is no longer a single point of failure, and its existing stake is actually protected instead of written off.

Principle:

Run-off doesn’t mean starvation. It means disciplined, selective support to protect and grow value where it still makes sense.

6. How Founders and Co-Investors React When a CVC Exits

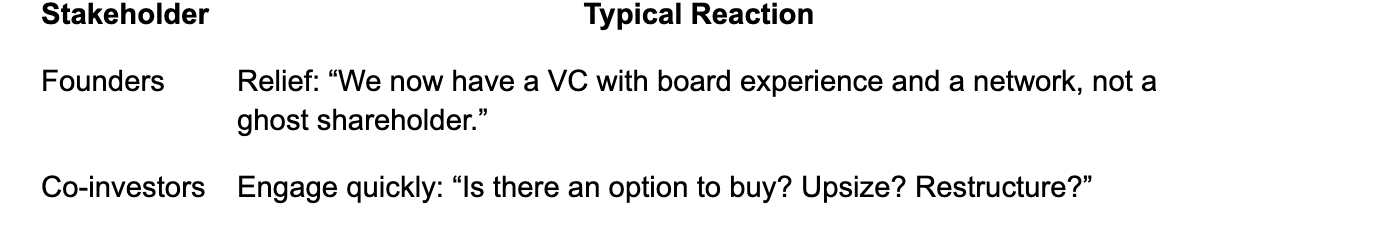

Martin is very clear on the human dynamics once a corporate announces it’s leaving VC:

Immediate reaction:

Founders: “We’ve lost a supporter; will we get any follow-on help?”

Co-investors: “Is there dead capital on the cap table?”

After Redstone steps in:

Everyone tests your limits

Co-investors want cheap upsizing

Founders may try to buy back stakes at discounts

Later-stage investors want to tidy cap tables

Redstone’s line: you can’t be “a seller at any price”.

The job is to keep value discipline while using run-off as an opportunity to:

Strengthen syndicates

Improve cap tables

Avoid panic selling

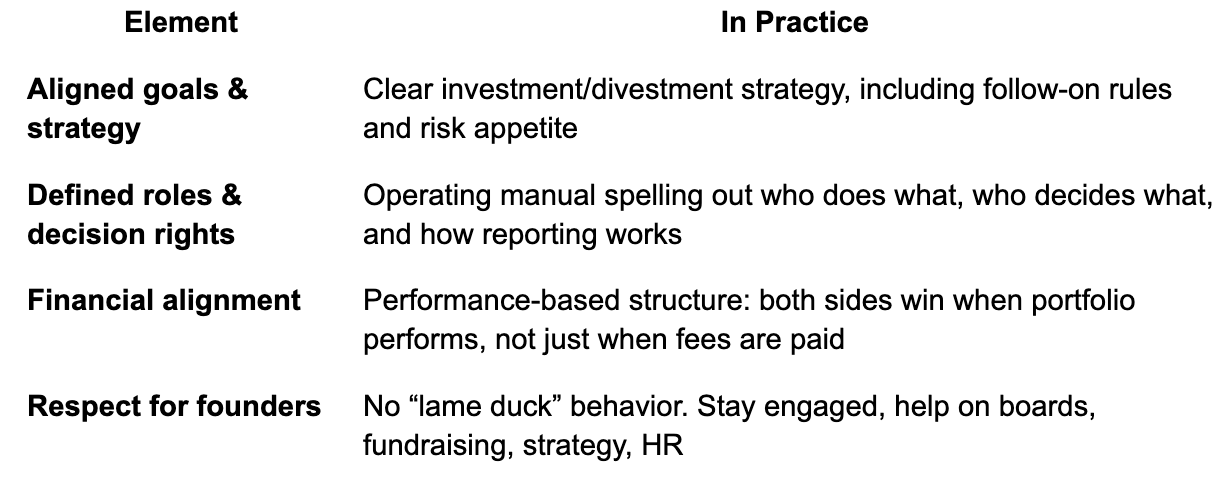

7. What Makes a Good Corporate–Redstone Partnership?

This came up both in run-off and active CVC work. The pattern is stable:

Without this, you either get value leakage or reputational damage — usually both.

8. Corporate LP vs Single-LP CVC: Know What Game You’re Playing

The conversation also touched on corporates as LPs in VC funds.

Martin draws a clear line:

Corporate as one LP in a diversified VC fund

Same LPA as everyone else

You can offer extra services (deal flow, strategic sessions, etc.), but you cannot skew the fund to solve that corporate’s internal pain points

Corporate as single LP

Very different game → this is CVC

Corporate can shut it down at will

Governance and IC must be designed to blend corporate and VC logic (e.g. mixed IC: Redstone partner + independent expert + corporate)

Key warning Redstone gives to other VCs considering corporate LPs:

Don’t let CVC become your “CRM team.”

CVC is for outside-in learning and strategic positioning, not for patching internal IT problems.

Use CVC to see where the best founders and most interesting money are going, not to fix this year’s SAP headache.

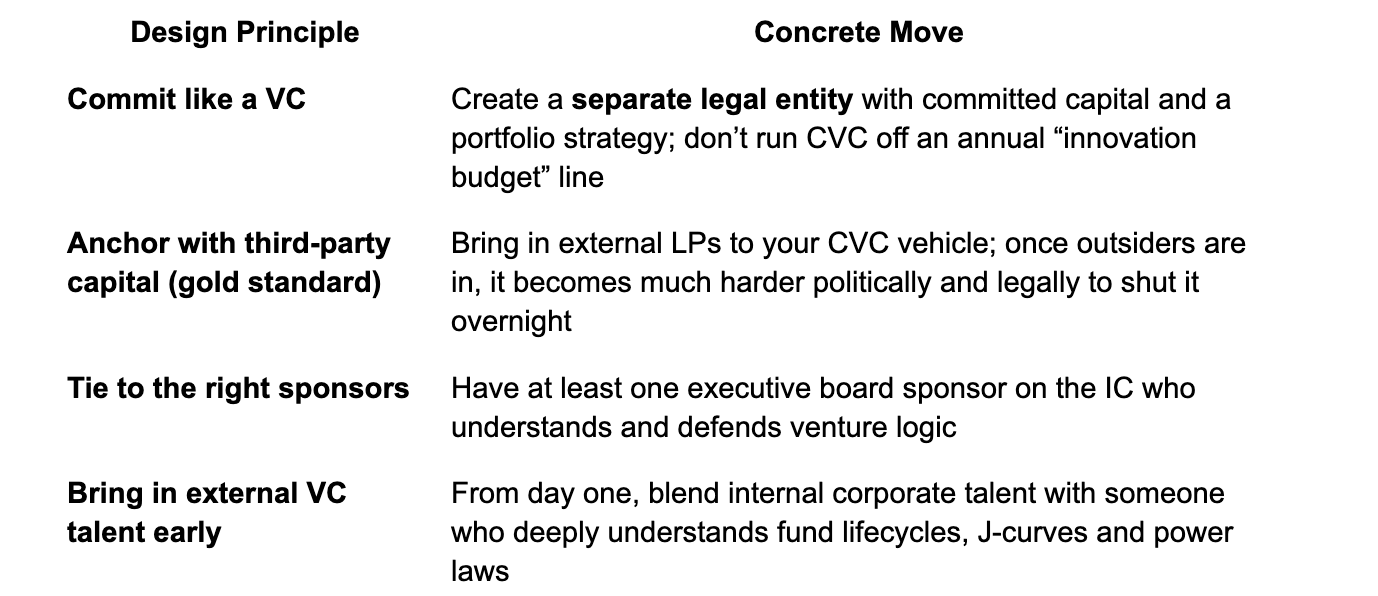

9. How to Design a CVC That Survives Longer Than 3.7 Years

The last part of the conversation zooms out:

How do you avoid winding down in the first place?

Martin’s answer is structural:

Jeppe frames it simply:

“Internally, it’s all about strategic alignment.

Externally, you still need to be a f***ing awesome financial investor.”

If you don’t clear both bars, you’ll eventually join the 3.7-year graveyard.

10. What Needs to Change in Europe?

The underlying question that runs under the whole episode:

Are European C-suites actually educated in what corporate venturing is?

In the US, many big corporates were once startups themselves. In Europe, much of the index is legacy. That shows up in:

Short time horizons

Lack of comfort with J-curves

Misaligned incentives (bonuses vs long-term value)

Martin’s mission with Redstone is to bridge VC logic and corporate logic, so that:

Corporates become better investors

Startups don’t get whiplash when strategies change

CVC isn’t just another short-lived initiative, but part of a serious innovation portfolio

If you’re:

Running a CVC

Thinking about shutting one down

Or considering taking a corporate as a major LP

…this conversation is worth a full listen.

👉 Listen to the episode at eu.vc

And if you share this with one person, make it the CFO or CEO who still thinks “venture” is just a line item in the annual innovation budget.