The Golden Opportunity in VC

A guest piece by Owen Reynolds of Teklas Ventures, the venture arm of the FO associated to Teklas.

This piece is a guest piece written by our good friend Owen Reynolds from Teklas Ventures, the VC arm of a family office associated with Teklas.

Owen is an economist by education and heart, and has worked at a similar regulatory commission as the US FERC. at the beginning of his career whereafter he made the change into VC, first investing in impact in the US and then later joining Expon Capital in Luxembourg to now finally have arrived at Teklas Ventures he invests in automation, robotics, and automotive, as well as broader industry 4.0, energy, and decarbonization.

In my hometown of Chicago, this spring is a spectacular cacophony, thanks to a variety of cycles clicking at the same time.

A BIZARRE SPECIES

Species of Magicicada, commonly known as cicadas, are having a bumper season. These large, winged, red-eyed, though largely harmless species are relatives of grasshoppers and locusts—though thankfully lack the penchant for devouring everything in their path.

Cicadas are a bizarre species that spring up from subterranean nests on multi-year cycles following a remarkably precise pattern. In addition to annual cycles, the Midwest has 13-year and 17-year sub-species.

The last time these cycles coincided was 1803—and the next time they will do so again is in 2245. Many expect this year to be louder than ever thanks to the secular shift of climate change.

All these cycles are combining at this very moment—creating a Golden Opportunity for cicada’s to have the most successful reproductive season in centuries. The rhythmic drill will be as loud as a gas-powered lawn mower—or worse.

EVEN MORE BIZARRE.

There's another bizarre species I belong to that is equally dependent on macro and micro cycles. This species gets a gut check every quarter and a public reappraisal every year at annual general meetings.

We reach an existential cliff every 3 years, know success only after 10 years, and forget the lessons of previous generations 25 years on, as wisdom sunsets. And we too are subject to the ebbs and flows of longer secular trends far beyond our control. Welcome to the Venture Capitalist species.

Much like Cicadas, the venture ecosystem is at the juncture of several cycles that have created another Golden Opportunity—in this case for LPs like myself.

As an LP, I’m not selling anything. You may even ask why I would bother telling you all this? Largely because I want to see a healthy, long-term investable pool.

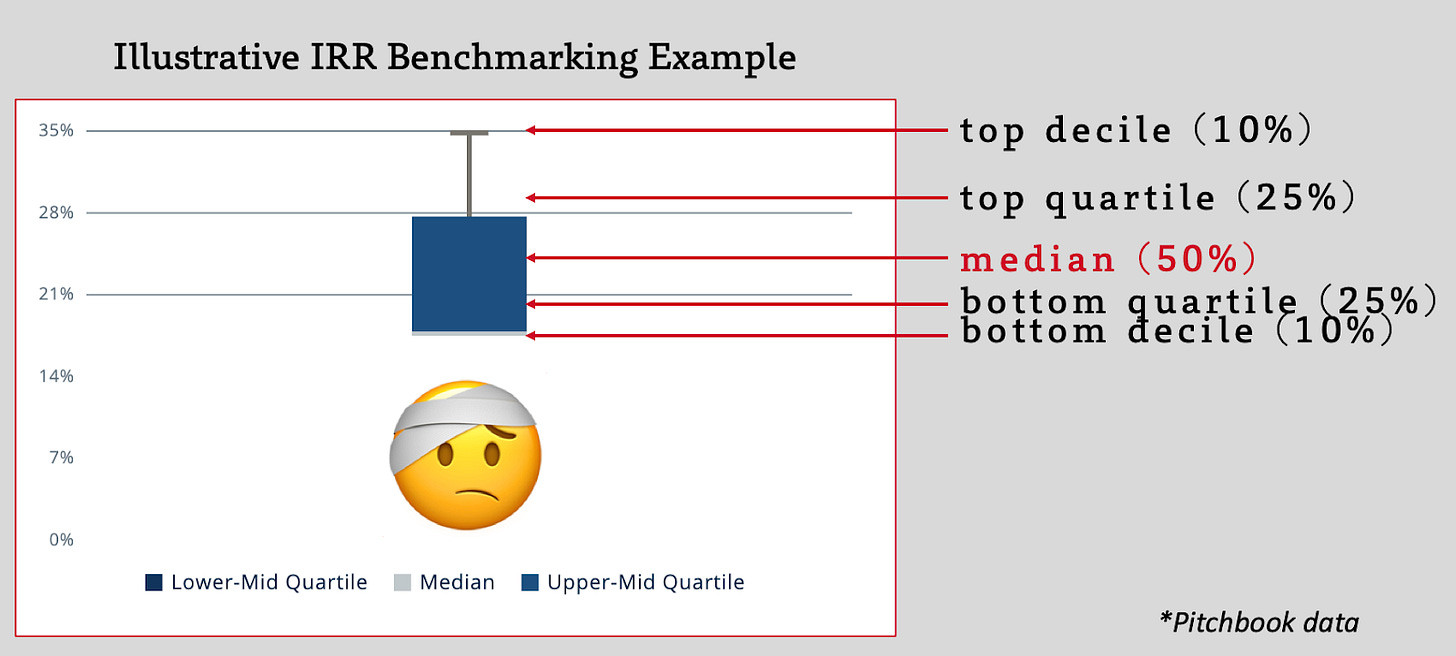

As a former GP, I'd long dreamt of true benchmarks for our companies–today's still nascent data-driven investing. As an LP, I now get to do exactly that using decades of data. As venture funds benchmark unit economics, LPs benchmark fund performance.

We benchmark previous fund and individual partner performance by IRR, total value of paid-in capital (TVPI) and distributed to paid-in capital (DPI). We study whether they were above or below the median and why that happened when it did? Were any of those top quartile, top decile? Is this sustainable?

We strip out top assets to see whether this was an accident, or whether we expect this to happen again—how “robust” the portfolio is. Were check sizes a help or a hindrance?

The exercise is cold, brutal, and tactical—with no room for fudging the numbers if you want to keep any intellectual credibility. And you may ask why it matters? Persistence.

Fund managers’ ability to replicate performance has been repeatedly studied by Professor Stephen Kaplan at University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business.

Kaplan looks at how previous performance correlates to future fund performance, by quartile. His team sliced the data in dozens of ways across venture capital and private equity, following individual teams, and their successive funds’ performance.

They found that top performing funds stay top performing funds. In other words, it’s not an accident and it’s not random (like private equity… but we’ll leave that for another day)

And it’s not just the Sequoias and the Benchmarks. It’s the industry. According to Kaplan, 45% of today’s top quartile funds are following the top quartile performance of previous funds. This is persistence.

Now, there are a thousand variables that can and do disrupt the significance of persistence. There’s a reason that the other 55% can’t replicate that success. But the trend holds water under even the recent tech downturn.

BRINGING THE SPECIES TO LIFE

Coming back to the real world, I’m sure I don’t have to remind you of how tough it’s been to fundraise for companies or venture funds since November 2022—the previous Nasdaq peak.

It’s not just a feeling that it’s harder than it’s been in ages. It actually is. LPs are overexposed and illiquid beyond just the impacts of any lingering denominator effect. Many haven’t been able to recycle potential liquidity from two funds ago as public markets have been traded for growth equity and private equity M&A.

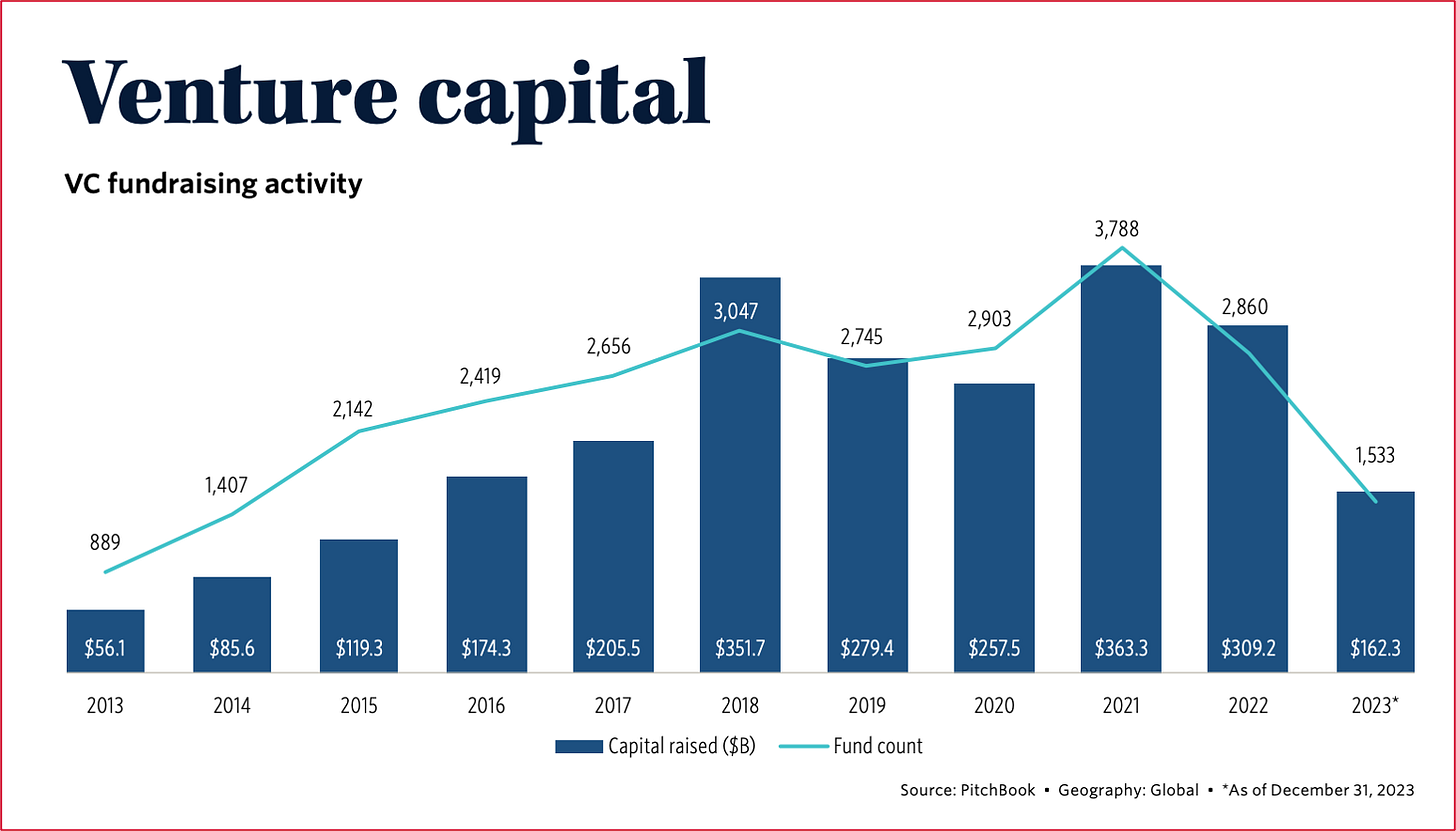

It's no surprise that funding allocations to GPs reflect that struggle. In 2023, venture GPs raised 55% less capital, and in 60% fewer fund closings than the peak in 2021, according to Pitchbook's figures below.

Top performing funds across Europe, I can testify, have finally had a wave of closes over the last 6 months. But most funds will struggle or are being left by the wayside.

One of the quirks of venture that stuck with me from my earliest days is that it’s the only job you need to reapply to every 3 years. No matter how good you are (or you think you are). No matter how strong your track record, your portfolio companies' references, and your network. No matter what, GPs have to ask for their jobs back every 3 years.

They have to ask LPs to trust them for another go at the wheel, another few cycles around the sun. And LPs need to decide whether they have the bandwidth, the budget, the risk-tolerance, and the geographic need to give you that job back.

The tough truth is that as capital flows into GPs has cratered. It’s a stark reminder to all of us in the venture capital species that we’re all out of a job after a cycle if we don’t perform.

An increasingly consensus conjecture is that this decrease will have a rather mechanical knock-on effect. If only about half the funding is coming through to venture GPs, those below the median are a relic of the last market cycle. The distribution could look something like this…

Half is admittedly a rough estimate—so make up your own minds about what the reduction will be. Pitchbook already estimates that in the US, there were already 38% fewer “active investors” in 2023 than a year before, or 2.725 firms disappearing. I expect the same trend in Europe.

As a result, the global venture ecosystem is being re-molded in a smaller, tighter, more efficient image. Funds are in flux. Underperforming partners are being cut. Top talent is migrating to where TVPI held up during the market correction. New funds are emerging to take the places of those that could not deliver. And it’s now easy to see which partners’ deals survived the tide going out. Identifying and accessing truly talented teams becomes the trick–not just indexing on the asset class.

HISTORY RHYMES

The last market cycle saw the same—an industry culling. Performance stagnated before and hit a trough during the Great Financial Crisis, but was boosted after the dust cleared. Identifying and accessing truly talented teams becomes the trick–not just indexing on the asset class.

The bottom quartile of funds floated around zero through 2010, about 18 months after the market bottom. That same year saw top decile performance over 40% IRR, which was surpassed again in 2012, as you can see below from Pitchbook data.

Venture funds take 6 - 18 months to raise and are deployed over 3 - 4 years. As the Nasdaq low was in February 2009, we can assume funds 12 - 18 months later, starting in 2010, escaped the impact. Similarly the Nasdaq low this time was in October 2022—19 months ago today.

ESPECIALLY IN EUROPE

In the US, everyone from family offices to pension funds are funnelling capital into VC, into innovation, into startups. Their hunger for high returns and wealth generation tilts the capital balance in favour of entrepreneurs.

In contrast, European funds are often squeamish about investing into these high risk assets.

On this side of the Atlantic, private funds' focus remains staunchly on wealth preservation instead of wealth generation. The assumption is often that as long as the family business is producing cash flow, it's generating wealth so no one else should be worried about doing the same.

Pension funds have a similar risk tolerance. There has been a lot of ink spilled on speculating why European pension funds don't invest much in venture either. In 2022, pension funds only allocated 0.01% of their assets under management (AUM) to venture! According to the 2023 State of European Tech, pension funds made up 3.3% of total VC funding, down from 4.9% in 2019.

The drop off may still be thanks to the denominator effect, but even the high water mark is a fraction of US pension fund investments. US Pension funds, as far back as 2001 provided 50% of venture investors' capital and accounted for 1.9% of their own pension fund's AUM.

At the same time, COVID lockdowns and a temporarily flat world only disconnected by time zone levelled up everyone. Each founder and venture investor was immediately compared to their best global (often US) counterparts, raising the bar ever higher for the next generation.

THE GOLD

Like the Cicada my Midwestern roots, this season is a rare combination of several critical cycles for the venture ecosystem.

We’re ending the 3 year cycle of managers who will sadly not be able to raise again, leaving only the hardiest of the species.

The average 10-year economic cycle (this one, sadly, way less precise than the Cicada) which came to an end made those left standing the clear next generation.

While the 25-year generational cycle saw partners sunset before the recent bubble, reminders of unit economic negligence will stay with the generation for decades.

European family funds and pension funds are leaving even the best venture investors underfunded, despite clear comparables to global funds during Covid.

A secular, 700-year-long trend of lower interest rates leaves everyone not guessing if central banks will lower interest rates, but when. (We'll leave this for a future post).

What that receding tide has left LPs in Europe is a Golden Opportunity to invest in venture. Unit economics and unit profitability matter again. Fund performance can be faithfully measurable for the first time in a decade.

The funds that are left in the market are being reshaped, cut apart, or self-shaping to be the leanest, highest performing vehicles in decades. Funds are formally leveraging their networks, sharing meaningful carry-on-interest portions with venture partners, scouts, and advisors.

And these funds are accessible in Europe. The supply-demand mismatch is large enough that there is plenty of room for family offices to get into not good funds, not great funds, but the best funds in Europe.

So why would I would share all of this?

The last market cycle ended badly — for everyone. I understand the funding environment in Europe completely dried up much more so than today. It killed off firms, leaving only those who could cling to the coattails of banks, but not necessarily entrepreneurs to guide the next generation.

While this time around is different, and we’re already out of the worst, I want a robust ecosystem. I want a competitive, aggressive ecosystem that replenishes itself naturally. So take advantage of this window of opportunity.

I cannot imagine a better time to be a venture capital LP.