Monetary Premium & Investment: Europe & US Divergence. Part 3.

A guest piece by Owen Reynolds of Teklas Ventures, the venture arm of the FO associated to Teklas.

This piece is a guest piece written by our good friend Owen Reynolds from Teklas Ventures, the VC arm of a family office associated with Teklas.

Owen is an armchair economist and leads Teklas Ventures, the venture arm of an automotive family office, covering both venture fund investment and direct industrial tech investment strategies. He is a former US Peace Corps Volunteer, founder of a sustainable construction company, and economist at the US FERC. After his MBA, he started in impact investing at an Omidyar fund in the US, then spent two fund cycles with Expon Capital in Luxembourg.

A major area of discrepancy between Europe and the US is the amount and the way investments happen. From the corporate level to households, investment decisions are made differently thanks to several structural reasons.

The amount of money saved is quite similar across the OECD—of course, with richer countries generally saving more. A difference though is that household savings in the US are funneled not towards true savings vehicles, but rather investments, with a heavy bias towards the home market. In contrast, the adage of old ladies saving cash under their mattresses is real in parts of Europe. The economic consequences are palpable for investors.

Valuation Gap

The difference in where money gets invested has an intuitive impact. We can see it in what has been called a valuation gap between Europe and the US. Why for example, do companies listed on US exchanges like the NYSE and Nasdaq get higher valuations than those traded on the Euronext, the LSE, or the DAX?

This analysis captures the depth of the (growing) valuation gap, as equities analyst Jay Younger wrote below. Stripping out even the top of the market, and just comparing the mid-cap European to US markets, the difference is clear.

MSCI Europe Mid Cap trades on a FY24 PE of 13.9x with expected EPS growth of 9.1% (PEG: 1.5x) versus MSCI US Mid Cap which trades on a FY24 PE of 18.4x with expected EPS growth of 6.5% (PEG: 2.8x).

The key takeaway isn’t just that US companies have higher price-to-earnings (FY24 PE) valuations, but whether that price comparison holds after accounting for growth. The PEG reference above is exactly that, the price to earnings growth ratio. It’s the share price compared to the expected growth of a company’s earnings—in aggregate, comparing the European and US mid-cap market.

In conversational parlance, even your average mid-sized company in the US is valued at 2.8x the today’s earnings to expected future earnings growth, as opposed to 1.5x in Europe. That’s an 87% premium! Are US companies really 87% more productive? Or 87% more likely to continue growing?

The Family Trickle Down

How families decide or are encouraged to consume, save, and invest is essentially the economy. In macroeconomics, family decision making—often called “consumption”—is the biggest single component. It reminds me of my father’s term for discretionary shopping, “fuelling the economy”. It was always toungue-in-cheek, though completely accurate.

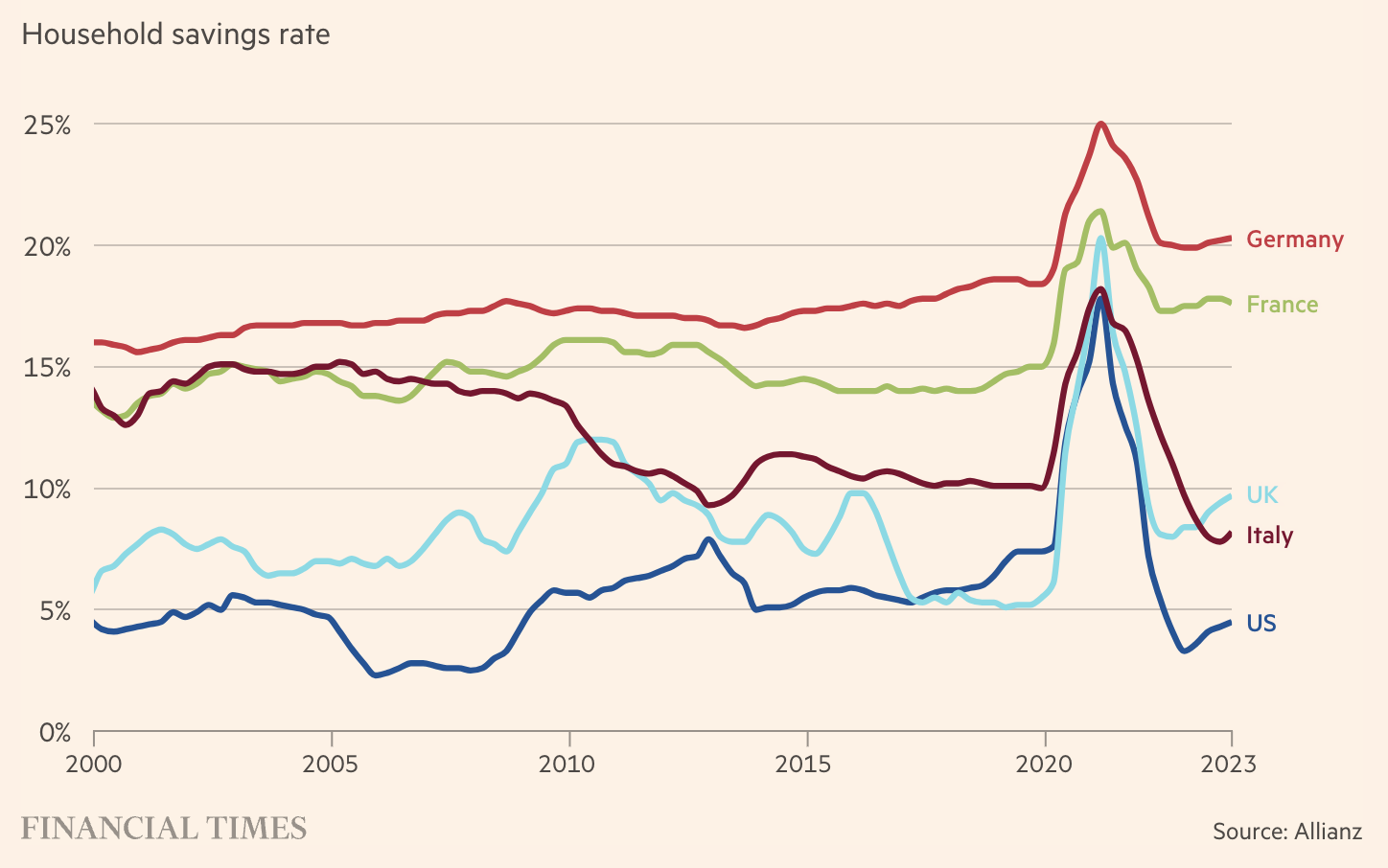

Many have seen graphics like this, with the US at the bottom of the savings chart. The US savings rate as a % of GDP is lower than most of Europe, and is intended to show savings under the mattress crowding out invested capital. However, the US GDP includes outsized health care costs at 17% of GDP and larger military expenditure at 3% of GDP.

So I prefer to use the graphic below. Comparing household savings as a percentage of household disposible income is what people choose to save as a percentage of what they can save, not as a percentage of the macroeconomy.

OECD countries save along a pretty tightly grouped spectrum, with higher income countries generally saving more, as shown below. Financial hubs Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Ireland lead the pack with over 20% of disposible income saved by individuals. The next grouping includes the Netherlands (18.8%), the US (17.5%), Sweden (17%), and Germany (16.5%), a structurally similar group. Australia, France, the Czech Republic, Korea, and Belgium also come in at over 14% of disposible income saved.

As you may (perhaps painfully) recall from macroeconomics, a country’s economy is defined as Y = C + I + G + (X − M) . Y is the GDP or total output, C = consumption, I = investment, G = government spending, X = exports, and M = imports. You may also remember that we can consider Y = C + S + T on the family side, where C = consumption, S = savings, and T = taxes. The result is C + S + T = C + I + G + (X − M)—so that the econmy is largely defined by (1) consumption, plus (2) total investment defined by private savings, plus (3) government spending defined by taxes, and (4) adjusted for the foreign trade balance.

If savings behavior across the OECD is so similar, shouldn’t investments in these countries be about the same, as well?

But of course “no”. The cost and productivity of that capital saved differs. For example, not all taxes become government spending. Debt can take a chunk straight out of that vis-à-vis interest payments on debt.

Similarly, savings is not exactly investment. Savings under a mattress crowds out proper investment (as the first graphic above is usually meant to show). A critical reason is because of how families save and invest. Family “savings” in a low/no-yield savings account, “savings” in a mutual fund vs. “savings” in an index fund vs. “savings” in direct stock picking all have very different impacts on aggregate capital markets. Their nuance defines just how productive that capital is for the economy.

The 401(k) and IRA Basics

A critical structural difference is the institution of 401(k) and IRA plans in the US. A 401(k) is a codified tax-advantaged savings plan. As opposed to a defined benefit plan that provides the same amount throughout your retired life, like a pension plan, these are defined contribution plans.

They are matched by employers (often doubling the invested capital), and have competed against traditional corporate pension plans in recent decades in the US. While there are socioeconoimic upsides and downsides to a plan that you can draw down early (with fees), borrow against, or reduce savings into, it is a big thing in the US.

IRAs are individual retirement accounts which are not employer-specific, or usually matched. But they do have tax benefits, so that a saver can be taxed on their retirement age salary (lower), as compared to their current (higher) salary.

Both 401(k)s and IRAs have some levers that have massive macro implications. They almost always offer “target date funds”, which stair step savers towards the classic 60/40 equity/debt portfolio, and match risk with age. Many of them also allow extremely simple access to index funds into either the S&P 500, the Nasdaq 100, or similar strategies. They may also offer some limited international or small cap stock exposure, but often have guardrails.

My 401(k)-type vehicle while I was a US Federal Economist allowed me to change my benefits going forward, but not going back, and had multiple risk limitations, protecting me from doing anything stupid. Similarly, the options included nothing of extreme risk—controlled access to equities, international stocks, and growth exposure at the highest end of the risk-return spectrum.

Monetary Premium

A report below on US household holdings shows the size of these defined contribution plans and IRAs on the US economy. With $8.14 trillion in defined contribution, and $11.5 trillion in IRAs, together they make up the lion’s share of financial asset retirement holdings in the US, funneling untold capital into equities over the decades.

Defined contribution plans like 401(k)s have significant corporate equities and mutual fund exposure. The defined benefit plans (like pension funds) are not unlike them. The impact of “savings” being truly invested into a range of debt, equity, and active management has secured a flow of capital into these markets for decades to come.

The $6.4 trillion in direct equities, and (assuming a 60/40 split) $5.4 trillion from mutual funds invested in equities, are from both defined contribution (65%) and defined benefit plans (35%). This combined $11.8 trillion in equities ownership represents 21% of the US’ combined $55.5 trillion public equities valuation.

Considering the fact that investors have a natural “home bias”—investing in brands we see close to home—we can assume most of those equities are indeed US equities. Even a conservative estimate that 20% of their holdings are international would mean 17% of US equities are owned by defined benefit or defined contribution plans—and 11.1% alone in defined contribution plans.

The impact?

This ownership is in addition to individual family holdings outside of these plans, employee stock options and company ownership, personal mutual fund holdings outside of these specific accounts, or international holdings.

These plans have allowed significant savings capital to be put to productive investment use, as opposed to leaving them under the mattress to rot. It has also very likely boosted the value of these markets, a “monetary premium”, a term I first heard on podcast Animal Spirits.

While I can’t imagine this explains all of the 87% valuation gap, it’s impossible that $11.8 trillion does not have a strong supporting role on US equities valuations. I’ll let smarter minds than mine tell you what the exact premium is—but let’s say it is non-negligible.

R&D & Investment

An extra 21% of savings invested into companies (not truly saved, but invested) and the other reasons for the 87% valuation gap have boosted US capital markets. One of the biggest knock-on effects is that US companies simply invest more in R&D. As shown below, as recently as 2022, McKinsey estimates that the top 10 largest US companies invest three times more than the top ten European companies.

Similarly, direct foreign investment (DFI) into Europe has decreased while it’s exploded in the US. As the graphic below shows, global investment decreased in 2020 during the pandemic, but recovered in the US while it decreased in Europe in 2022 and 2023.

The structure of forced investment schemes seems draconian, and many of the socioeconomic concerns are well justified. However, it has funneled badly needed capital to productive uses while bolstering valuations in the US compared to Europe. The 401(k) and IRA structure may offer critical support for the US’ unique capital markets.

This is part of a series on the divergence of the EU and US economies and the impact on innovation and startups from one investors perspective. Feel free to read Owen's previous posts on Culture, Reserve Dollar Discrepancy, and Monetary Premium & Investment.