PORTFOLIO CONSTRUCTION (and a final word on REGULATION). Part 7. The EU & US Divergence

A guest piece by Owen Reynolds of Teklas Ventures, the venture arm of the FO associated to Teklas.

This piece is a guest piece written by our good friend Owen Reynolds from Teklas Ventures, the VC arm of a family office associated with Teklas.

Owen is an armchair economist and leads Teklas Ventures, the venture arm of an automotive family office, covering both venture fund investment and direct industrial tech investment strategies. He is a former US Peace Corps Volunteer, founder of a sustainable construction company, and economist at the US FERC. After his MBA, he started in impact investing at an Omidyar fund in the US, then spent two fund cycles with Expon Capital in Luxembourg.

I’ll get this out of the way. My American positivity makes me cringe at deconstructive “Euro-bashing”, so I’ve avoided it in this series. The entire motivation behind these posts was to detail some of the structural economic reasons behind the US innovation economy decoupling so distinctly from Europe’s—not the usual bemoaning.

However, it would be a particularly “rose-tinted glasses” perspective to write a seven-post series without pointing out this unfortunately structural issue. Yes, European regulations slow innovation, kill companies, and kill the motivation to innovate.

Germany is perhaps the worst offender. Reading out every page of your shareholders agreement at the notary before signing, bank’s inability to fathom cash-losing entities, rules on recognized revenue, requiring everything to be hard (paper) copies, and an inability to fire underperforming staff without bribing them to stay quite are just the top of my list. Recent reforms on employee stock options spares me some ink on that, thank heavens.

It is a broader problem of fostering a bureaucracy to embed itself in ways that were efficient at the time of that bureaucracy’s creation—not today. Many of these outdated regulations leave European startups default dead.

I’ll admit there are significant positive benefits to some regulations on the quality of life. And I used to be a regulator in the US, so I’m not saying they shouldn’t exist. However, that same security blanket that coddles the weak dampens the flames of the exceptional. It kills motivation to start something new—or risk it all in trying.

The innovation economy relies on the exceptions, the exceptional, and their inherent motivation to change some corner of the world.

Portfolio Construction

This series of posts, regulation included, boils down to one thing—portfolio construction.

Without significant capital at the risk end of the risk-return spectrum from big capital allocators, there is no innovation finance. Without risk, there is no R&D in large corporates, there is no venture capital, there is nothing ventured and nothing new.

According to Atomico’s State of European Tech 24, Europe’s pension funds committed €637m into global VC in 2023—some of which certainly went to US funds. This global exposure represents only 4,1% of the €15,4b raised by venture funds in Europe in total, and is diluted by the pension funds’ US exposure.

But it’s not that Europe doesn’t have serious fire power. To put this into scale, VC commitments by Europe’s pension funds is a measly 0,007% of AUM, on average. There is some regional variation, shown below, with DACH once again disappointing, in comparison to the 0,02% allocation by CEE neighbors to the East.

And this is already against the backdrop of pension funds doubling their commitments to VC in Europe, though down from the peak in 2019. According to Atomico’s State of European Tech 24, global pension fund commitments to European VCs doubled between 2015 and 2023, as shown below.

How does this compare to US pension funds?

In a paper exactly 20 years ago, Gilles Chemla wrote “Pension funds have long been a major source of capital to private equity funds. At the end of 2001, over 50% of capital investment to venture capital funds in the U.S. came from pension funds…”

So, 20 years ago, American VC funds were getting half of their capital from pension funds, while today European VC funds are getting only 4%.

This has diversified over the years in the US, as endowments and family offices have become bigger parts of the ecosystem. However, Europe’s lack of endowments and the relatively risk-averse attitude of many family offices leaves that side of the equation lacking as well on this side of the pond.

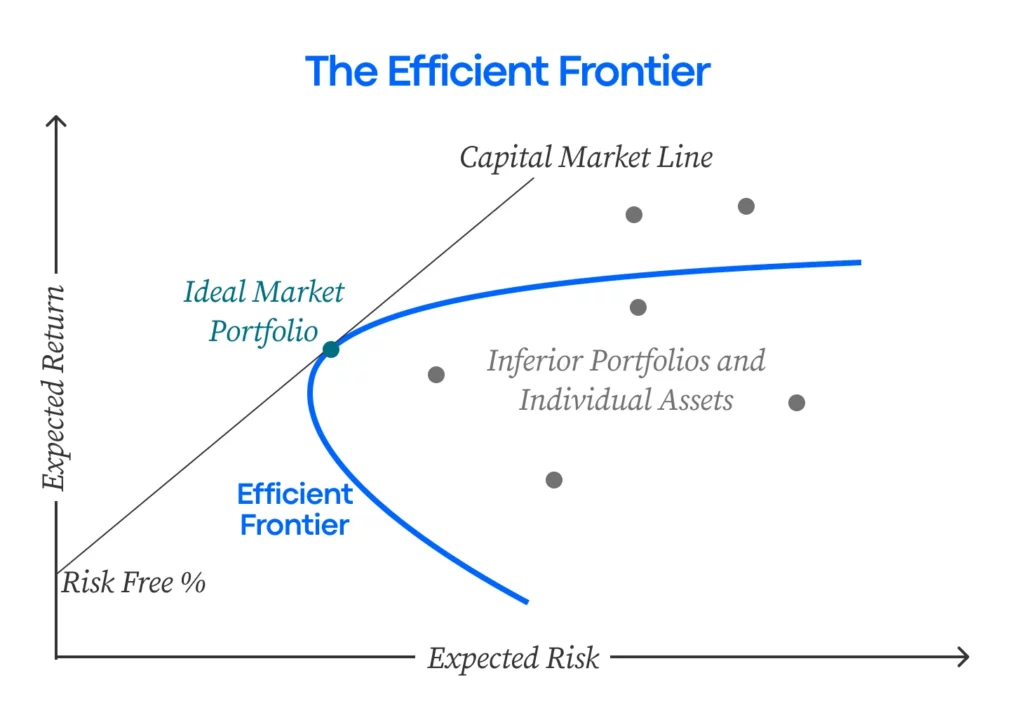

On both sides of the pond, investors are taught the risk-return spectrum, shown below. This academic allocation strategy was first developed by Harry Markowitz in 1952, to support logical, diversified investments for these types of long-term funds. Imagine that private real estate, private equity, venture capital, and crypto are all asset classes further up and to the right from emerging markets equities show below.

As a result of Markowitz’ research, investors are taught to (1) understand our portfolio’s risk tolerance, (2) pick the highest returning point (tangent) along that risk curve, and then (3) invest along that entire curve programmatically until the exposure size no longer justifies the economics to hire the required expertise, assuming a long horizon. (Thanks Linqto for the graphics!)

This would imply that investors should diversify across the asset class spectrum, adjusting to their risk tolerance.

It’s no surprise, the academic research in Europe points towards the same thing and increased exposure into VC (often lumped together with its bigger sister, PE). Investment & Pension Europe recommends the asset class as a great opportunity.

And Europe’s largest pension fund, Norges Bank, had a team of academics pour through historic returns, the global landscape, and economic research that puts this blog series to shame. Their recommendation clearly favored increased exposure into PE & VC:

We documented that PE fund performance historically has exceeded public equity index returns (without further correcting for differences in risk) for both buyout and venture, and in both the U.S. and Europe. For U.S. data, the average buyout fund delivered 20% higher distributions over the life of the fund, compared to a strategy that invested similar amounts in the S&P500 index with the same timing. The average VC fund delivered 35% higher distributions than the corresponding S&P500 strategy over the life of the fund.

Despite all the evidence needed, time and time again I hear pension funds, family offices, and other allocators saying they “don’t do PE”, “don’t allocate to venture”, “or don’t take on that kind of risk”.

The results are an artificially truncated portfolio, which will inherently underperform. If you assume a long-term time horizon, then it follows you can weather the storms of market volatility. But if investment managers choose not to follow the academic evidence, they are preserving wealth at a nominal value but losing it in relative terms. The only wealth preservation strategy over time is wealth creation, which requires risk.

WHY?

So why don’t European investors invest as much as American investors into venture capital and private equity? These are theoretically rational, professional investors. And pension funds are particularly under exposed to high growth, high risk assets.

There are several logical reasons for European fund managers to decrease exposure into venture relative to American peers. In Culture, we walked through history and the impact education has on the innovative economy and risk tolerance. Dollar Reserve Discrepancy details a critical advantage to investing in uber-productive industries like tech and biotech enjoyed by the US.

The Monetary Premium & Investments goes on to show secured capital flows from savers to markets that boost valuations in the US. The Land of Liquidity expands on that to connect higher valuations to increased liquidity in the US. And Structured Failure puts risk culture in context.

The best talent is better compensated in the US thanks to hiring up and the structure to fail and try again. Similarly, capital is structured to buoy market valuations, offering greater liquidity and higher chances of stock-based compensation. This all puts the US at a competitive advantage for funding innovation.

But that only explains part of the story.

One additional variable is a link between compensation and allocation, driving a major problem in allocating to high-risk, high-return sectors. Fear appears to be driving intellectual dishonesty at the allocator level (pension funds, endowments, family offices).

Thanks to the “hiring up” mentality, American allocators are frequently offered significant upside. They receive bonuses, salary boosts, and carry-on-interest (a type of upside participation bonus that is tax-advantaged) for making high conviction investments into the right companies and the right investment teams.

It may cost you your job if you’re wrong. But it’s worth “going out on a limb” when you have that conviction, as long as the upside is there.

Many of Europe’s pension funds are very much treated like public servants. They may have bonuses at the top, but many of the junior staff spend years training in indifference—instead of training in conviction. Generation after generation of CIOs (Chief Investment Officers) are trained to play it safe and keep their job, decreasing risk and the incentive for increasing exposure in the face of decades of research.

That is reflected in salaries of CIOs between the US and Europe. According to Business Insider, 40% of family offices are paying their CIOs $1m or more, compared to only 6$ in Europe. The results “based on surveys of 635 family office leaders, didn't find any CIOs in the UK, Middle East, and Australia making as much as chief investors in the US”. Similar anecdotes are peppers across the investment team compensation press.

Takeaway

There are a lot of ways that Europe and the US are different. But in recent years the markets have diverged in a way that seems obvious in hindsight, but didn’t seem obvious only a few years back.

This post series goes through some of the structural components that have caused the divergence. Some are fixable—while others we’ll just have to live with. I’ll leave the fixing for smarter minds and bigger teams. Meanwhile, I’ll continue to put capital where it counts and invest into venture capital.

Thanks so much for these articles Owen. I have devoured each one. I live in Europe, but work for a U.S. VC and have felt on my skin not just the cultural differences in my risk appetite and approach to venture, but also how my finance education did not prepare me for the risk/return paradigm the way my U.S. colleagues see it. I had to re-learn my understanding of markets and liquidity, and I can say that your posts are spot on on a number of items